Sometimes Taking The Penalty Is The Smart Play

/About a month ago, crime fiction author, Frank Scalise (Zafiro) stopped by to share his story, Twenty and a Day, of retiring from the police department to pursue his passion of writing.

Frank also had some ideas he wanted to share about retirement. Since he's way ahead of me in retiring, I figured I should hear what the man has to say!

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more by reading my disclosure.

I love hockey. As I write this, the third round of the playoffs is in full swing and the only thing that isn’t awesome about it is that my team isn’t playing. Sad face emoticon.

As in all sports, there are rules. Sometimes players break those rules and there is a consequence. In hockey, that usually takes the form of a player being sent to the penalty box for a period of time and his team being shorthanded on the ice for the duration of that penalty. It is a pretty significant disadvantage for the team that is down a player, and sometimes it results in a goal against (statistically about 1 in 5 times, but that varies depending on how good the players are). Once in a while, the shorthanded team will score (a much, much lower statistic that I am too lazy to Google at the moment). The outcome of a game can turn on a penalty and a resulting power play goal. Coaches bench players over it. The ‘skate of shame’ back to the player’s bench from the penalty box after a goal is scored during a penalty the player took is one of the most dreaded moments a player can experience. Generally, it is considered a bad idea to take a penalty.

Generally.

Imagine, though, if a team’s goalie has overreacted to the play and is way out of his net. The opposing team gets the puck to a forward on the opposite site of the ice and that player is looking at a yawning net. He’s basically salivating at this point. There’s no time for the goalie to get back into position to make a save. It’s a sure goal. Now, imagine you’re the defenseman, also beaten on the play. You’ve got two choices. Let him shoot and score, or reach out with your stick and hook an elbow or a leg to prevent it. Conventional wisdom says don’t take a penalty. But when you take that penalty in order to prevent an almost-sure goal, it is recognized as a ‘good’ penalty. The player still has to sit for two minutes and the team is still down a player, but no goal is scored on the play. And even though a power play opportunity represents a 1 in 5 chance of a goal, those odds are a heck of a lot better than 1 in 1 the player was facing before. In taking the penalty, the player goes against conventional wisdom because conventional wisdom doesn’t work in this scenario. He takes the penalty and his team is in a better situation for it.

Okay, so how does this equate to wealth? I mean, it’s hockey. But actually, there is a parallel in our income building world. I’m faced with that same situation a little more than a year from now, and I think it is something most people will also face, though they may not be looking at it quite right.

Most retirement funds, public or private, have either an age at which you can draw or some combination of age and years of service. Whatever that draw point is, it represents when you can start taking your pension at full value. But many plans also have an early draw provision, in which you can draw at an early age, but at a penalty. Conventional wisdom says not to do this. You lose money. Hang in there and don’t draw until you hit the full pension criteria.

In other words, don’t take a penalty.

Sometimes, though, you have to at least consider whether it might be a good penalty to take. Let’s look at a specific example – mine. Now, we’re going to work with round, made up numbers of dollars here because it is easier math and because who shares their actual finances, anyway, right? But the formulas are all real.

In my retirement system, you get 2% per year of service toward your pension. Your pension is based upon your highest contiguous five years’ earnings. That’s why you’re not vested in the system until the five year mark. For most people, the highest five years come at or near the end of a career, but the system doesn’t care when your highest five occur, just what the number is. For easier math, let’s say my financial average salary was $100,000. And since I worked for twenty years, and earned 2% a year, my pension is 40% of that $100,000, which is $40,000/yr. That’s what I can draw at 53 years old, without penalty.

However, my pension is one of those with an early withdraw option. You can start drawing as early as age 50, but there is a penalty. The penalty is 3% per year before age 53. Now, that’s not 3% as in ‘I only earned 2% a year, so I’m losing a year and a half…damn, that’s $3000!’ No, it is a 3% penalty on the actual amount you are drawing, which in this case is $40,000. What’s 3% of $40,000? $1200, or $100/month.

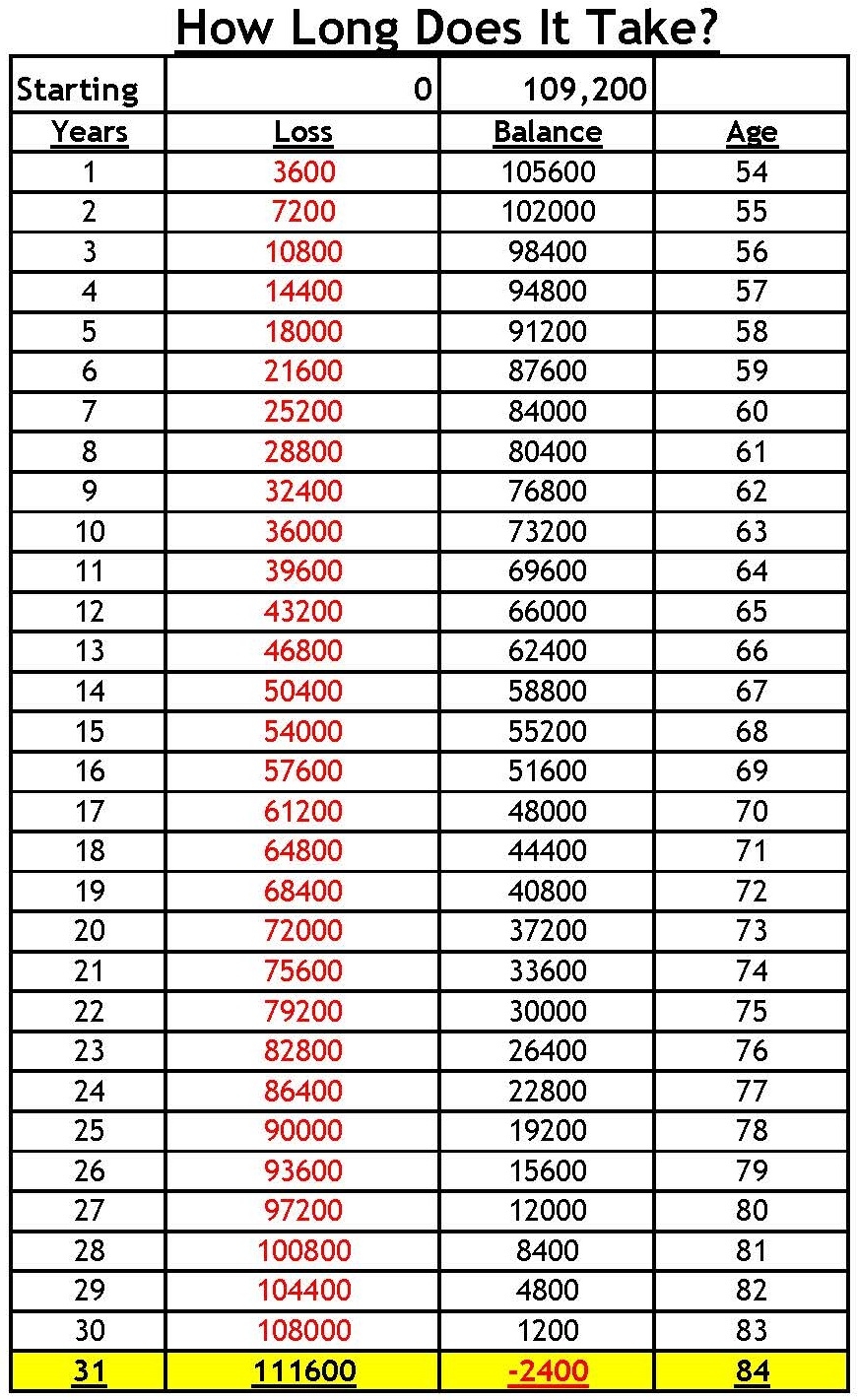

Check out Table 1 as we walk through this part. If I follow the conventional wisdom and draw at age 53, I earn $40,000/year, or $3,333/month. If I draw at age 50, I incur a 9% penalty on that $40,000, which equals $3,600 or $300/month. That means I draw $36,400/year, or $3,033/month.

Does that sound like a bad plan to you? It does to many. They see the loss of $3,600 a year and that’s the end of it. But they are forgetting something very important. I’ll be drawing that reduced pension for three full years (age 50, 51, 52). Under the conventional wisdom of waiting to age 53, I’d be drawing zero. Zilch. Nada.

Anyone good with numbers will point out that in the long run, I’ll earn more by waiting until age 53 and taking the full draw. And they are mathematically correct. If the lifetime earnings on this deal are the number one goal, age 53 and a full draw is the way to go. But let’s run those numbers to see if there isn’t more to the equation. Something deeper, and ultimately more important.

If I earn $36,400 a year for three years (age 50, 51, 52), that’s $109,200 of earnings over that three year period. So at the time I hit 53 and start to withdraw at the point I would have if I followed conventional wisdom, I am already $109,200 to the good. I can’t think of a hockey analogy here so think of it as playing with house money. I’ve earned $109,200 that I never would have if had I waited until age 53 to begin drawing my pension.

But as many of you are no doubt correctly pointing out, I still have to start serving my penalty (there’s my hockey analogy again. It’s back!). And as we’ve already established, my penalty is $3600 a year (or $300 a month – see Table 1). That’s how much less I’m making now because I chose to draw early.

So the big question is, how long before that penalty is equal to my house money?

The math isn’t hard. Let’s look at Table 2. I lose $3,600 a year (Loss) against an earnings total of $109,200. Thus, after the first year of losing $3,600, my gain/loss is still $105,600 to the positive (Balance). And I’ve just turned 54.

So how many years does it take before my lifetime earnings on this deal goes from black to red?

Thirty years. 30.33, to be precise. Again, check out Table 2, all the way at the bottom.

As you can see, I’m approaching 84 years old when my lifetime earnings from this pension go into the red. That has to make you start to think about whether this is very possibly a good penalty to take. I like to think I’m as immortal as the next guy, but what’s the life expectancy for a man in my demographics today? Even more specifically, you can go to the Social Security Online website, punch in your gender and birthdate and get an estimate. I did it. You know what my estimated life expectancy was? 82.2 years.

So house odds say I’ll shuffle off this mortal coil more than a year before I start losing money on this deal. That alone is a motivator to take the money at age 50 and run.

But let’s get even more morbid. What if I die sooner than 82? Well, then I come out even further ahead on the deal.

And if I live significantly longer? Yeah, I eventually lose more money, true. But I’m still alive, so that’s something! And in both instances, I think we’re forgetting another important point. For three years (age 50, 51, 52), I drew a salary, albeit penalized, that I wouldn’t have already drawn. That’s $36,400 per year versus zero per year. For three years! If I die well before 82, then I’ll be glad I had those three years to enjoy the fruits of my labor. And if I live to one hundred, I’ll be glad to be alive and I’ll still be glad I enjoyed the fruits of that labor for those three years. I expect most of us are considerably spryer at 50 than at 80, and more likely to have adventures. Adventures made possible by the fact that I had an income during those three years.

The reason I’ve considered this, and the reason everyone should, revolves around finding that balance between responsible finances and quality of life. I think the above paragraph clearly illustrates how quality of life is enhanced in this situation well beyond the financial ‘loss.’

How does this apply to you? Does it? As in all things in life, your mileage may vary. Your pension will have different parameters. Your monthly income needs will not be exactly the same. You may love your job and want to keep working. But the idea still applies. Most people have Social Security, for example. What I’m saying is that if there’s an early withdrawal option for your pension (and there is for Social Security), even with a penalty, don’t reject the idea out of hand. Run the financial numbers and the life odds and see how things lay out for you and your situation. Conventional wisdom will urge you to wait, and sometimes that’s the right thing to do. But you won’t know unless you take a hard look at it. And if you do, there’s a chance you might find that the goalie is way out of position, the net is yawning for the shooter, and that this is, in fact, a good penalty for you to take.

What about you?

Are you for taking the penalty or

waiting to get full benefits of

whatever system you're in?

We'd love to hear from you.

To find more about Frank Scalise / Zafiro, please visit his website at www.frankzafiro.com

He’s also on Twitter at @Frank_Zafiro and Facebook at facebook.com/frank.zafiro